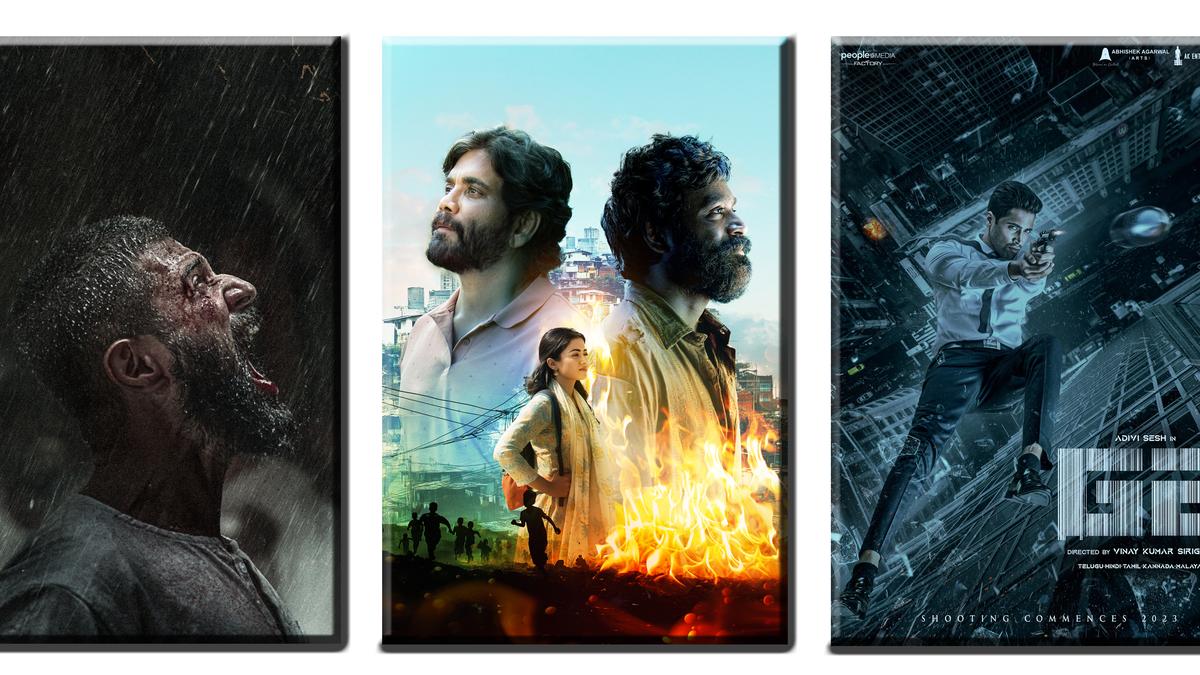

The Long Walk Review

The Long Walk is bleak... even by Stephen King standards. Here's our review.

It may not have been the first book the Master of Horror ever published, but The Long Walk was the first novel Stephen King ever wrote. Written during the height of the Vietnam War, it’s a fascinating, primal keystone text for understanding the lens through which King sees the world, and all that remains relevant about the text - translated faithfully by director Francis Lawrence and screenwriter JT Mollner - allows this long-overdue adaptation to punch above the weight its barebones premise may suggest.

The rules for the 50 young men who’ve won a nationwide lottery to compete in the Long Walk are simple: Walk. Don’t stop, don’t sleep… walk. If a walker drops below three miles per hour, interferes with another walker, or otherwise breaks the rules, it’s a warning. Three warnings, and you “get your ticket.” In most cases, that means a bullet to the brain courtesy of the military escort riding along in humvees, led by The Major (Mark Hamill), a roaring parody of machismo and rugged individualism who’s something of a godhead in this ailing world.

The more the Walk winds on though, and as the elements and the limits of the human body come into play, the better that bullet starts to look for the set-upon young men. Lawrence - who cut his teeth on dystopic fiction with I Am Legend and most of the Hunger Games movies - kicks the Walk off within moments of the movie starting, but takes his sweet time before letting the first contestant get eliminated, a moment he punctuates with a cinematic flourish that lands as a real surprise so long after the movie has started. Every drop of rain, hill, dropped ration, and bowel movement that follows become life-or-death modifiers of the march.

The dozens of deaths that occur as The Long Walk goes are covered plainly and unflinchingly, and by the time the Walk has wound down to its final contestants, the ones who “got their tickets” early on look like the real lottery winners. Lawrence rarely lets viewers off the hook, squeezing every drop of blood out of that R-rating and forcing the viewer to be complicit in the violence. Even when we don’t see the carnage, Lawrence puts the focus on the terrified faces of the survivors, highlighting the mounting psychological weight being loaded onto them as their bodies start to fail. The violence doesn’t take long to become numbing, but that’s the whole point here. The director smartly illuminates this by having Cooper Hoffman’s Ray Garraty call out the real horror of The Long Walk early on, vocalizing his fear that both the Walkers and the audience (in their world, and by extension our own) will grow to accept the bloodshed as routine. Simple though it is, the conceit of The Long Walk proves a very elastic premise onto which many types of societal adversity can be projected.

Garraty’s reasons for joining the walk, and why winning matters to him, are a lot more complicated than most of his other competitors, which leaves him more open to forging relationships with the other Walkers, in particular Peter McVries (David Jonsson). Garraty and McVries spend much of The Long Walk musing on the larger existential questions begged by the very existence of the competition, and both Hoffman and Jonsson bring easy naturalism to their performances, which winds up being a real saving grace in the midst of all this darkness. The support and kindness they show each other become infectious, leading to moments of triumph as small as sharing food or letting one lean on the other.

It also makes the times when they’re at odds feel as dangerous as the creeping exhaustion they’re both fighting, as that camaraderie feels more and more like the real secret to getting out of this thing alive (even if the rules state only one of them would be able to make it in the first place). With Garraty’s attention set to how his single wish could change the world if he wins, Jonsson’s McVries becomes the real heart of the film, putting lovely emphasis on the power of living moment to moment and finding silver linings to every thundercloud… even the ones that dump rain on the boys as their shoes begin to fall apart and their feet start to bleed.

Garraty and McVries’ fellow walkers don’t get nearly as much depth, and here Lawrence and Mollner feel a little stuck figuring out how much time to invest in developing characters with presumably such short life expectancies. Even more prevalent characters like Olson (Ben Wang) and Baker (Tut Nyuot), who take to Garraty and McVries’ optimism, are mostly just there to reinforce the co-protagonists’ viewpoints. Barkovitch (Charlie Plummer) is an antagonist in the truest sense of the word, a nervy, annoying nihilist who The Long Walk uses to needle at the competitors, positioning him as a ticking time bomb, poking holes in Garraty and McVries’ attempts to keep morale up, but he never quite goes off the way the movie seems to want you to think he will. Garrett Wareing's Stebbins, a strong, quiet contender for the win, is a much more interesting character in that respect: his usual silence makes any infrequent observations about the futility of hope or his own thorny motivations to walk hit a lot harder. Mark Hamill’s Major is drawn pretty thin, and the fact that he’s got the privilege of being driven around on the back of a jeep while the boys die walking gives you everything you need to understand what The Long Walk’s trying to say through him.

The Long Walk runs relatively short at 108 minutes, but it feels every second of it. The rinse-and-repeat nature of the deaths may hold a lot of emotional weight here, but rarely has the hairsplitting thought of shaving 10 or even five minutes off a cut felt like it may pay greater dividends as the pace does start to drag in The Long Walk’s second half. Gorgeous though the practical locations may be, Lawrence is only able to squeeze so much visual variety out of those long, verdant stretches of road, though he does break up the drone of the Walk with occasional flashbacks to Ray’s home life which explain why he was so adamant to join the Walk in the first place. These flourishes aren’t the only changes Constant Readers will notice. But the detours Lawrence takes from King’s source material are all additive. They stay in the spirit of the book and feel respectful to the story, rather than an attempt to change anything just for the sake of it.

Though the focus and perspective rightly stays on the Walkers, Judy Greer’s Ginny Garraty has a few opportunities to show up in support of Ray and, hey, no shock for anyone who knows thing one about Judy Greer, but she absolutely crushes in these very brief appearances. Greer’s quick shifts through all of the complex emotions a mother in this world may possibly experience, watching her boy take part in this death march, bookend the story, and are as haunting as any bullet or hemorrhage the movie has to offer.